The advertisement of the junk food is increasing at a high rate and it is aggressively exposed to the children. According to different research, Australian children are being bombarded with aggressive marketing for the junk foods which are considered as too unhealthy to be sold to children in many countries (Russell et al. 2020). According to a study published in the “Journal of Public Health Nutrition”, there is a direct relationship which exists between low-nutritional-value packaged foods and high levels of child-targeted marketing. It can be found out that assignment help Canberra and that In Australia; more than 95% of junk foods which are used for marketing techniques directly addressed to children would be prohibited from being sold to the children in any other country, just because those are unhealthy in nature (Ertz & Le Bouhart, 2022). In accordance with this discussion an example of Mexico as well as Australia can be given in this context.

In 2020 Mexico has made it mandatory and clears to have a “warning label” on all food products that exceed the energy, salt and fat and sugar thresholds. Foods that have a warning label can’t be sold to children, not even on the packaging or in other advertising forms. But on the contrary, the rules and regulations of Australia on their junk food marketing are optional and do not apply to their supermarkets like Coles or Woolworths where those junk foods are totally available and children can easily choose those (Kelly, Bosward & Freeman, 2021). Moreover, there are also no restrictions on using characters and celebrities, graphic design, giveaways or competitions on child-friendly packaging which attach the children more. In relation to this discussion it can be found out that the junk food industry is exploiting the “pester power” of the children within Australia which further shows that there is a statistically significant and strong effect on the grocery shopping decisions of the parents. The junk food organisations across Australia are enabling the food industry to capitalise on the emotional connection of the children to different characters, and their natural sweet and salty preferences. Thus, from a better understanding of this kind of scenario it can be stated that this is a public health crisis in the making where there is no legislative protection in place in a proper way (Trapp et al. 2022).

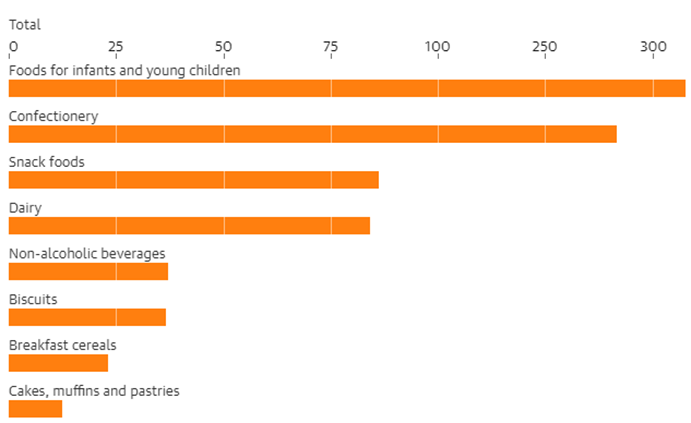

Figure 1: Categories of Foods for Direct Marketing to Children in Australia

(Source: theguardian.com, 2024)

An “in-depth review of Australian supermarkets’ on-pack marketing” has further depicted that an extensive as well as unregulated utilisation of child-targeted promotional tactics, assignment help Brisbane such as cartoon characters, most often on unhealthy and highly processed foods linked to overweight and obesity which is considered as an ongoing issue within Australia. In countries where more stringent food marketing regulations have had a positive effect on children’s eating habits, this practice is strictly prohibited (Richmond et al. 2020). This analysis of child-targeted food marketing clearly portray that there is a potentially damaging regulatory gap in Australia when compared to even some low-income countries. This regulatory gap in the food market is creating more constraints for the children, especially the teenage people.

In relation to this, again several researches have given the example of Mexico. According to those results, there are almost 96% of the products which have been surveyed might have at least one health warning symbol on their packaging in Mexico. This is because the rules are the strictest in the world and it would not be allowed to be advertised to the children in Mexico at all, not even on packaging or in other media such as television and print advertising. From this kind of scenario, it can clearly see that there is a good and tight regulation for the children to become healthier (Vanderlee et al. 2021). Furthermore, this result highlights the high prevalence of child-targeted promotional strategies which might be used to push the unhealthiest products to Australian households. In accordance with this discussion, one should note that it might come as a shock to parents and carers that the current “Australian regulatory system” does not provide any kinds of robust protection for the health of the children of this country in their near future from harmful on-pack marketing, unlike other countries that have enforceable on-pack marketing rules in place (Gascoyne et al. 2021).

Based on the above discussion, it can be seen that there are several researches which have been conducted by different research bodies within Australia. According to those studies, the abundance and aggressive promotion of ultra-pre-packed foods and drinks is considered as a key contributing factor to childhood obesity in Australia (Kent et al. 2022). Furthermore, it has been found out that there are about one in four Aussie kids and teens are overweight or obese which is further bringing them more negative future.

The researchers in this context have compared the health of products which have been used “child-targeted marketing” to those that did not. In this regard, those researchers have used four indicators to evaluate the health of products, namely, “Australian Health Star Rating System”, “Nova Classification System for Degree of Processing”, “World Health Organization’s Nutrient Profiling Model for the Western Pacific Region” as well as “Mexican Nutritional Profiling Model” (Lwin et al. 2020). As a result, those researchers have found out that the products which are using “child-targeted promotional techniques” have scored low on all of these indicators. In accordance with this discussion, it can be seen that under the “WHO model”, there are only 6.1% products which might be allowed to be sold to children and but, again, assignment help Australia under the “Mexican criteria”, there are only 4.5% products are eligible. This entire scenario means that if Australia adopted the similar legislation as Mexico it might mean that there would be almost 95.5% products which are advised to remove the child-targeted marketing elements (Chung et al. 2022). Thus, considering this kind of scenario, it can be stated that, the Australian government needs to establish some kinds of regulations which might help the children of that country to live a better and healthy life in future.

Reference list

Chung, A., Zorbas, C., Riesenberg, D., Sartori, A., Kennington, K., Ananthapavan, J., & Backholer, K. (2022). Policies to restrict unhealthy food and beverage advertising in outdoor spaces and on publicly owned assets: A scoping review of the literature. Obesity Reviews, 23(2), e13386. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/obr.13386

Ertz, M., & Le Bouhart, G. (2022). The other pandemic: a conceptual framework and future research directions of junk food marketing to children and childhood obesity. Journal of Macromarketing, 42(1), 30-50. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/02761467211054354

Gascoyne, C., Scully, M., Wakefield, M., & Morley, B. (2021). Food and drink marketing on social media and dietary intake in Australian adolescents: Findings from a cross-sectional survey. Appetite, 166, 105431. https://nscpolteksby.ac.id/ebook/files/Ebook/Journal%20International/Marketing/Appetite/Food%20and%20drink%20marketing%20on%20social%20media%20and%20dietary%20intake%20in%20Australian%20-%20Volume%20166%2C%201%20November%202021%2C%20105431.pdf

Kelly, B., Bosward, R., & Freeman, B. (2021). Australian children’s exposure to, and engagement with, web-based marketing of food and drink brands: cross-sectional observational study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(7), e28144. https://www.jmir.org/2021/7/e28144/

Kent, M. P., Hatoum, F., Wu, D., Remedios, L., & Bagnato, M. (2022). Benchmarking unhealthy food marketing to children and adolescents in Canada: a scoping review. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 42(8), 307. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9514213/

Lwin, M. O., Yee, A. Z., Lau, J., Ng, J. S., Lam, J. Y., Cayabyab, Y. M., … & Vijaya, K. (2020). A macro-level assessment of introducing children food advertising restrictions on children’s unhealthy food cognitions and behaviors. International Journal of Advertising, 39(7), 990-1011. https://www.andrewzhyee.com/publication/2020ija1/2020ija1.pdf

Richmond, K., Watson, W., Hughes, C., & Kelly, B. (2020). Children’s trips to school dominated by unhealthy food advertising in Sydney, Australia. Public Health Research & Practice, 30(1). https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5830&context=sspapers

Russell, C., Lawrence, M., Cullerton, K., & Baker, P. (2020). The political construction of public health nutrition problems: a framing analysis of parliamentary debates on junk-food marketing to children in Australia. Public health nutrition, 23(11), 2041-2052. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10200508/

theguardian.com, (2024), Australian children exposed to aggressive marketing of unhealthy foods – study, Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/nov/14/australian-children-exposed-to-aggressive-marketing-of-unhealthy-foods-study#:~:text=The%20study%20found%20the%20unprecedented,adolescents%20are%20overweight%20or%20obese. [Retrieved on 24.12.2024]

Trapp, G., Hooper, P., Thornton, L., Kennington, K., Sartori, A., Wickens, N., … & Billingham, W. (2022). Children’s exposure to outdoor food advertising near primary and secondary schools in Australia. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 33(3), 642-648. https://cancerwa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Trapp-2021-Childrens-exposure-to-outdoor-food-advertising-near-primary-and-secondary-schools-in-Australia.pdf

Vanderlee, L., Czoli, C. D., Pauzé, E., Kent, M. P., White, C. M., & Hammond, D. (2021). A comparison of self-reported exposure to fast food and sugary drinks marketing among parents of children across five countries. Preventive Medicine, 147, 106521. https://davidhammond.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/2021-IFPS-Marketing-Parents-Prev-Med-Vanderlee-et-al.pdf